ALL POSTS

Real, live scientists sharing cutting-edge research and related classroom activities.

Strike Up the Band (Structure)

Scientists are working to develop electronic devices that store and process information by manipulating a property of electrons called spin—a research area aptly known as spintronics. The semiconductors we are developing will not only be faster and cheaper than those used in conventional devices, but will also have more functionality.

Heat Flow and Quantum Oscillators

Materials that are absolutely perfect—in other words, materials that contain no defect of any kind—are usually not very interesting. Imagine being married to a saint: you would quickly be bored out of your mind! Defects and impurities can considerably change many properties of materials in ways that allow a wide range of applications.

CHASING THE MYSTERIOUS AND ELUSIVE LIGHT HOLE

Semiconductors are materials with properties intermediate between metals and non-conducting insulators, defined by the amount of energy needed to make an electron conductive in the material. The non-conducting electrons occupy a continuum of energy states, but two of these states (the “heavy hole” and “light hole”) are nearly identical in energy. The heavy hole is easy to observe and study, but the light hole eludes most observers.

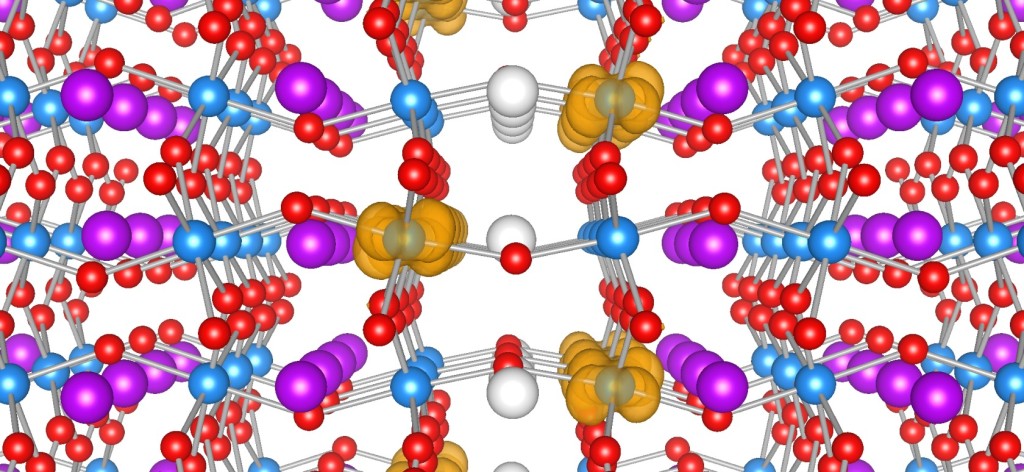

How to Turn a Metal Into an Insulator

Solids are generally divided into metals, which conduct electricity, and insulators, which do not. Some oxides straddle this boundary, however: a material's structure and properties suggest it should be a metal, but it sometimes behaves as an insulator. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara are digging into the mechanisms of this transformation and are aiming to harness it for use in novel electronic devices.

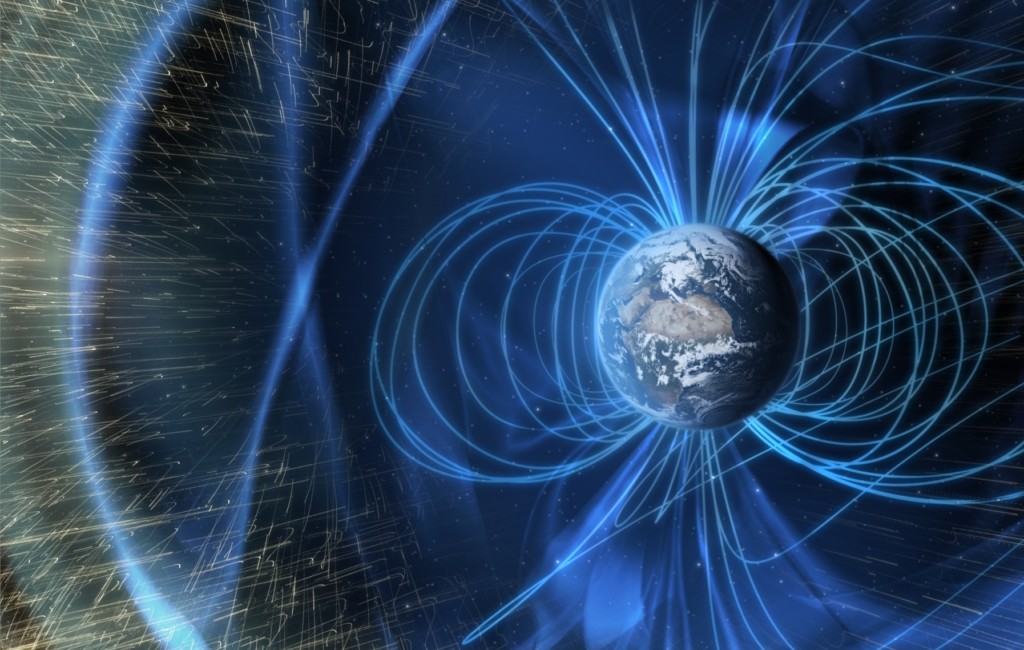

Imprinting Memory in Nanomagnets by Field Cooling

You may know that the media used in magnetic recording technologies, such as computer hard drives, are made of millions of tiny nanomagnets. Each nanomagnet can be switched up or down to record bits of information as ones and zeros. These media are constantly subjected to magnetic fields in order to write, read, and erase information. If you have ever placed a magnet too close to your laptop or cell phone, you know that exposure to an external magnetic field can disrupt information stored this way. Did you know that it is possible for the nanomagnets to "remember" their previous state, if carefully manipulated under specific magnetic field and temperature conditions? Using a kind of memory called topological magnetic memory, scientists have found out how to imprint memory into magnetic thin films by cooling the material under the right conditions.

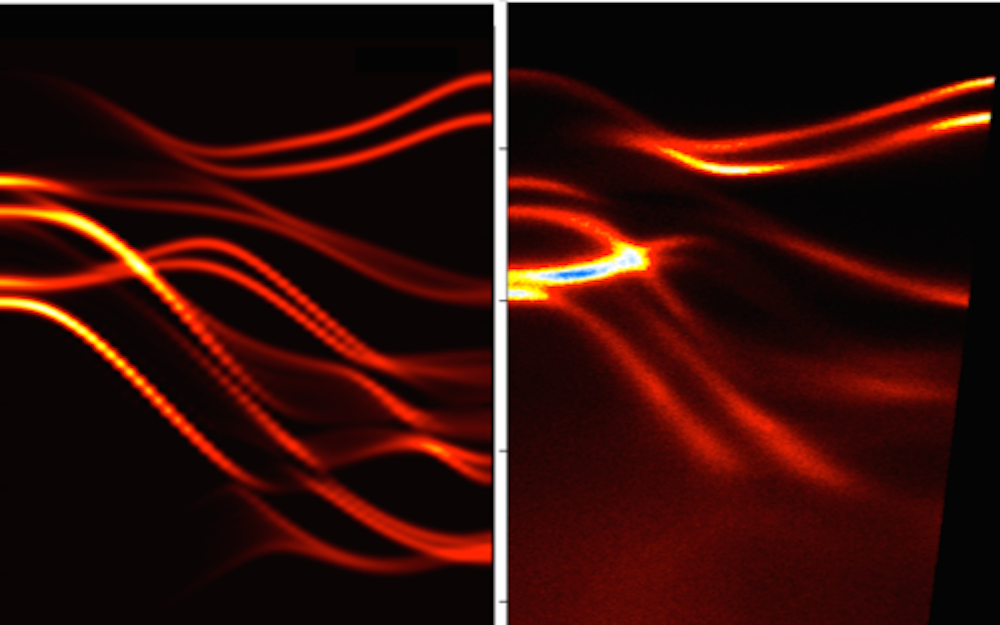

Gravity for photons

Inside solids, the properties of photons can be altered in ways that create a kind of "artificial gravity" that affects light. Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh tracked photons with a streak camera and found that whey they enter a solid-state structure, they act just like a ball being thrown in the air: they slow down as they move up, come to a momentary stop, and fall back the other way. Studying this "slow reflection" will allow us to manipulate light's behavior, including its speed and direction, with potential applications in telecommunications and quantum computing technologies.

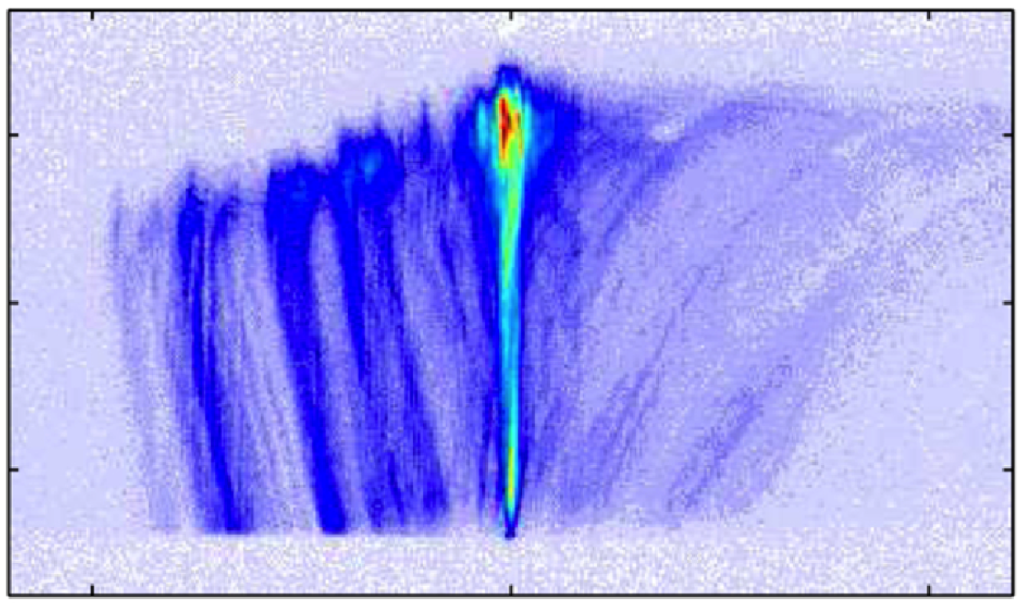

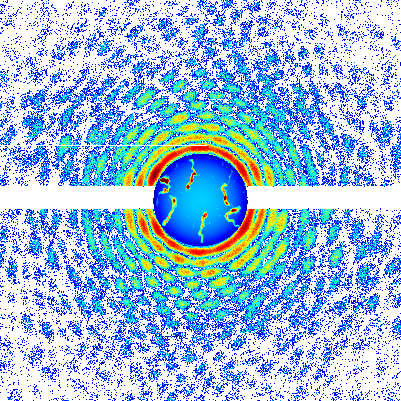

Hunting Quantum Tornadoes with X-rays

In a unique state of matter called a superfluid, tiny "tornadoes" form that may play an important role in nanotechnology, superconductivity, and other applications. Just as tornadoes are invisible air currents that become visible when they suck debris into their cores, the quantum vortices in superfluids attract atoms that make the vortices visible. Quantum vortices are so small they can only be imaged using very short-wavelength x-rays, however.

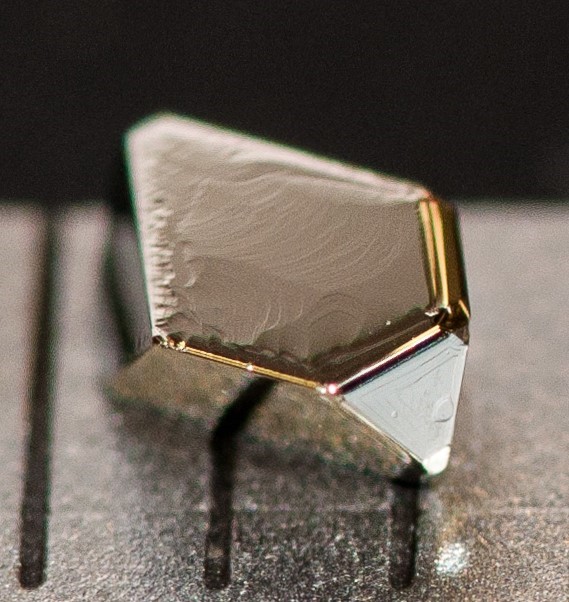

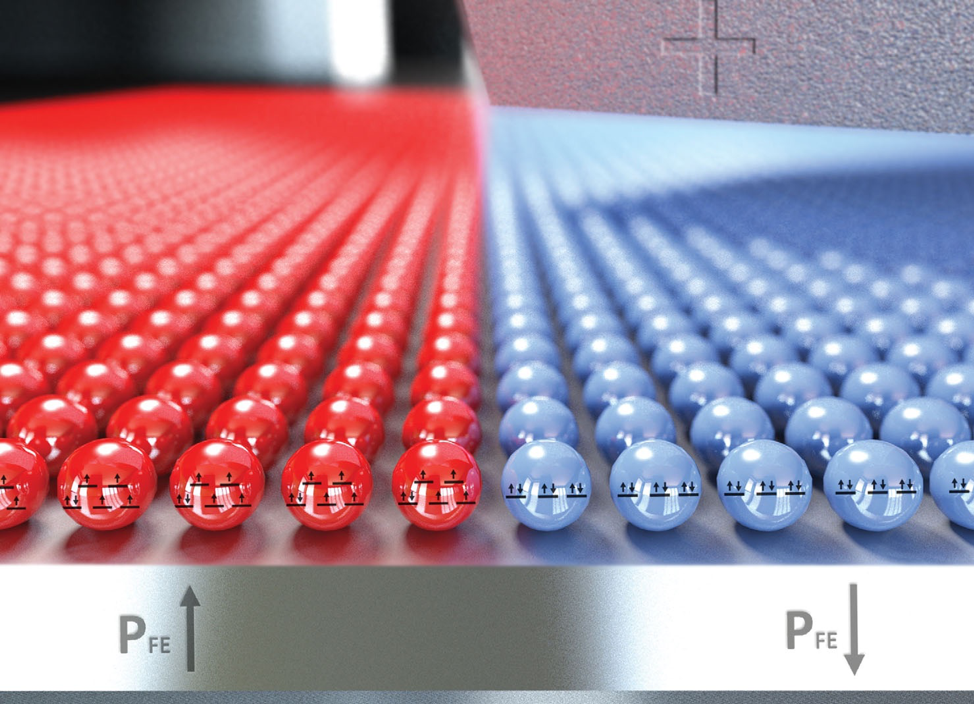

Straining for More Stable Memory

Would you rather have data storage that is compact or reliable? Both, of course! Digital electronic devices like hard drives rely on magnetic memory to store data, encoding information as “0”s and “1”s that correspond to the direction of the magnetic moment, or spin, of atoms in individual bits of material. For magnetic memory to work, the magnetization should not change until the data is erased or rewritten. Unfortunately, some magnetic materials that are promising for high density storage have low data stability, which can be improved by squeezing or stretching the crystal structures of magnetic memory materials, enhancing a material property called magnetic anisotropy.

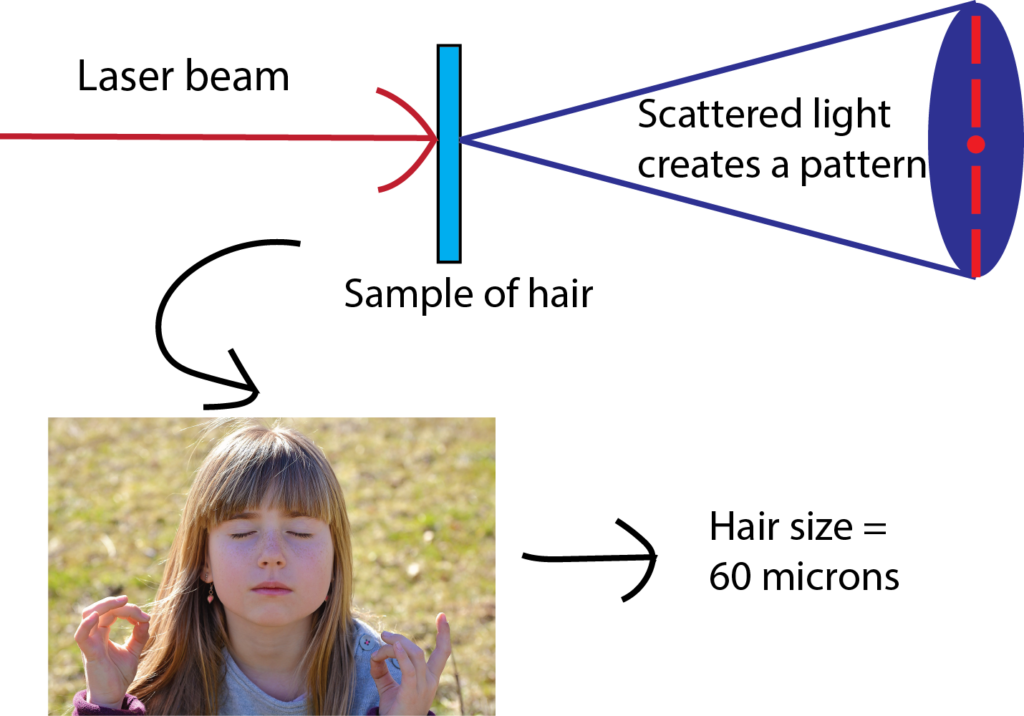

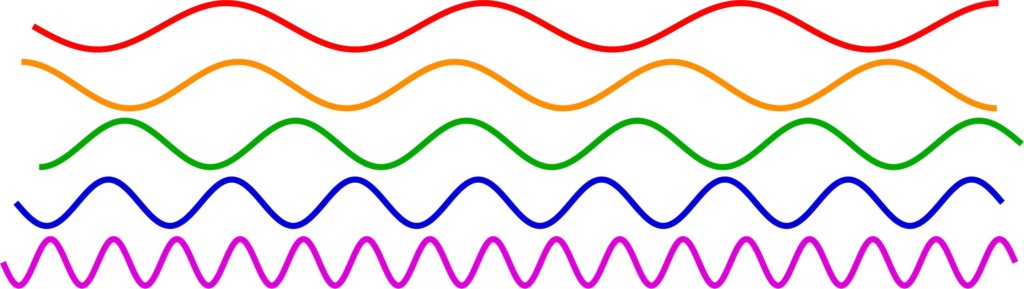

Use a laser pointer to measure the thickness of your hair!

Have you ever wondered how scientists can accurately measure the size of very small objects like molecules, nanoparticles, and parts of cells? Scientists are continually finding new ways to do this, and one powerful tool they use is light scattering. When an incoming beam of light hits an object, the light "scatters," or breaks into separate streams that form different patterns depending on the size of the object. This incoming light might be visible light, like the light we see from the sun, or it might be higher-energy light like X-rays. The light from commercial laser pointers, it turns out, is perfectly suited to measure the size of a human hair!

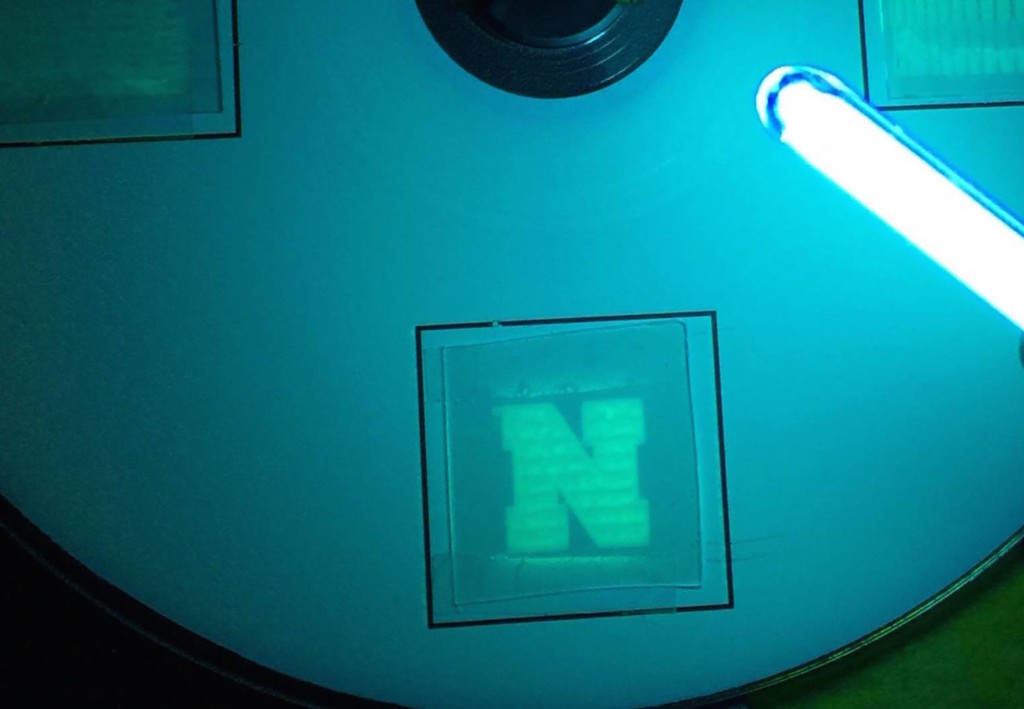

The Adventures of Solar Neutrons

Neutron radiation detection is an important issue for the space program, satellite communications, and national defense. But since neutrons have no electric charge, they can pass through many kinds of solid objects without stopping. This makes it difficult to build devices to detect them, so we need special materials that can absorb neutrons and leave a measurable signature when they do. Researchers at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln are studying the effects of solar neutron radiation on two types of materials on the International Space Station (ISS), using detectors made of very stable compounds that contain boron-10 and lithium-6.

The future of solar energy is . . . an inkjet printer?!

To increase our use of solar energy, we need to create more efficient, stable, and cost-effective solar cells. What if we could use an inkjet printer to fabricate them? A new type of solar cell uses a class of materials called perovskites, which have a special crystal structure that interacts with light in a way that produces an electric voltage. We've developed a method to produce perovskite thin films using an inket printer, which in the future could pave the way to manufacture solar cells that are surprisingly simple and cheap.

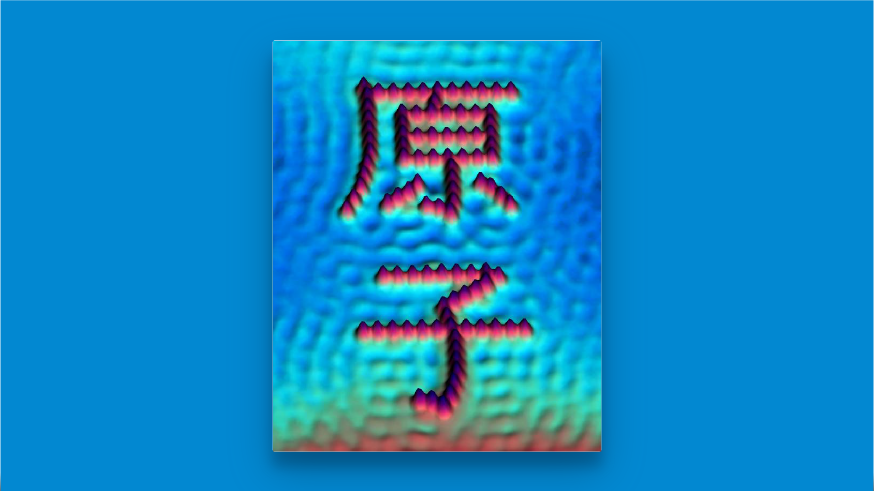

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy

You’re lining up your phone to take a picture of your dog. Light comes down from the sun, bounces off the dog, and into your camera lens, allowing you to take the photo. Your eyes work similarly, taking in all the light particles, known as photons, that are scattering off of objects in the world. Most things “see” by detecting these bouncing photons, which is why both you and your phone have a hard time seeing anything at all when the lights are off.

Magnets, Gatorade, and the Quest for Energy-Efficient Computers

Fool's gold is a beautiful mineral often mistaken for gold, but recent research shows that its scientific value may be great indeed. Using a liquid similar to Gatorade, it can be turned into a magnet at the flick of a switch! Read on to learn more!

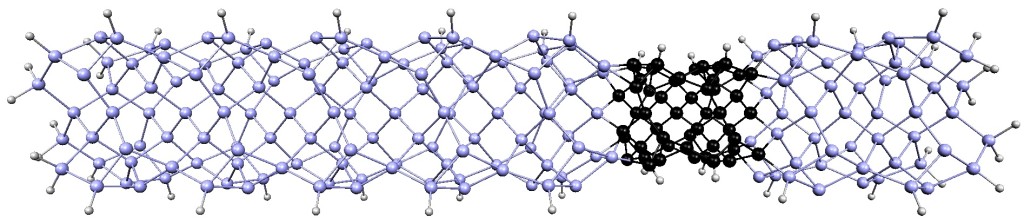

A Molecular Switch

Think of the hard disk in your computer. Information is stored there in the form of magnetic "bits." But do you know how small a magnet can be? Some molecules make magnetic magic, and these special molecules may give rise to the ultrafast, high precision, low power devices of the future.

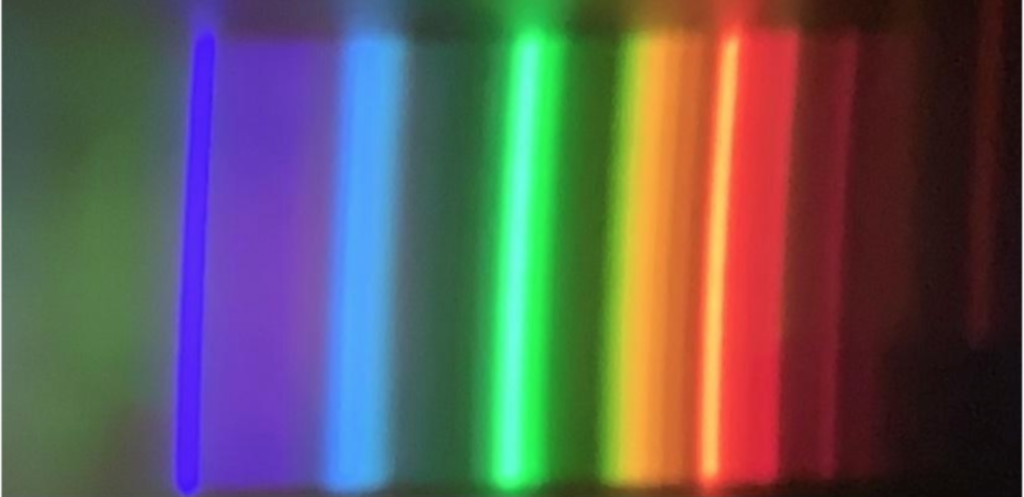

Coloring INSIDE The Lines

Have you ever wondered why shining light on a glass of water causes rainbows to appear? Or noticed the colors that reflect from a CD or DVD? In this lesson, you will make an instrument called a spectroscope that can separate light into its hidden components. You will also be able to use the spectroscope to understand why different colored objects and light sources appear the way they do.

How to Make a Giant Bubble

For the past two decades, giant bubble enthusiasts have been creating soap film bubbles of ever-increasing volumes. As of 2020, the world record for a free-floating soap bubble stands at 96.27 cubic meters, a volume equal to about 25,000 U.S. gallons! For a spherical bubble, this corresponds to a diameter of more than 18 feet and a surface area of over 1,000 square feet. How are such large films created and how do they remain stable? What is the secret to giant bubble juice? Click to find out more!

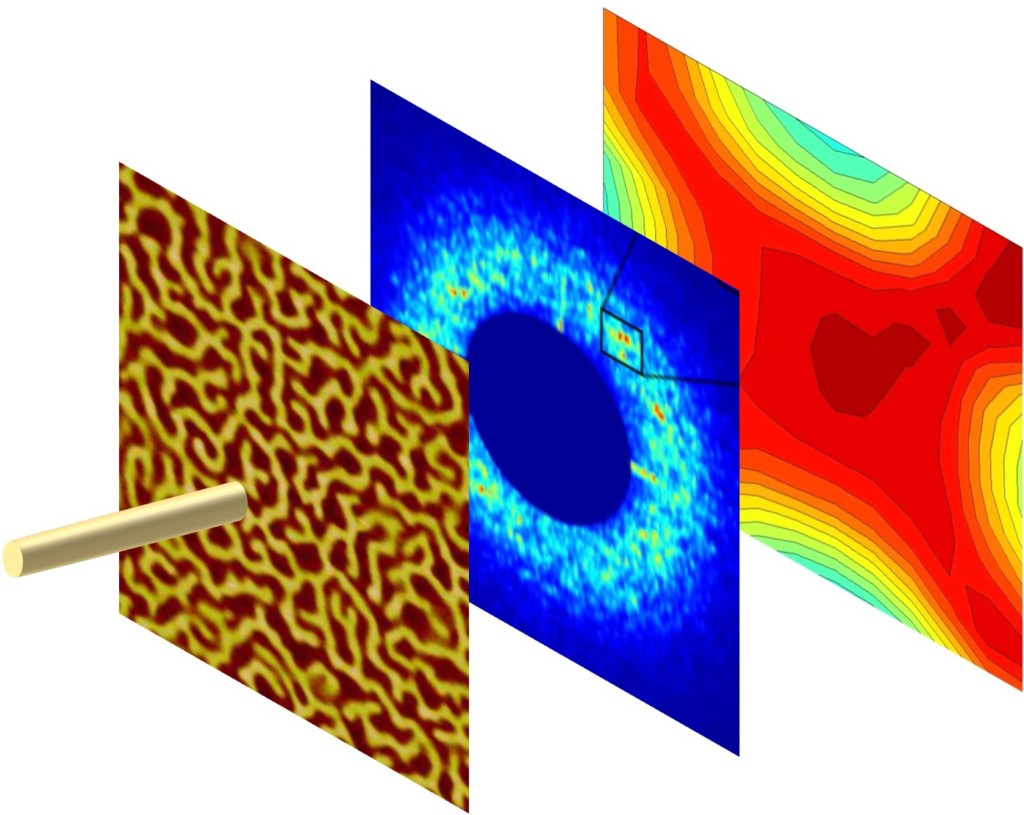

From Nanowaffles to Nanostructures!

How can you fabricate a huge number of nanostructures in a split second? Self-assembly is a fast technique for the mass production of materials and complex structures. But before self-assembly is ready for prime time, scientists need to establish ways to control this process, so that desired nanostructures emerge from the unstructured soup of basic building blocks that are fast-moving atoms and molecules.

This photon walks into a crystal . . .

When light strikes a material, electrons may be ejected from the material. This is called the photoelectric effect, and it’s the basis for many different technologies that convert light energy into electrical energy to generate current. In addition, the photoelectric effect is useful to scientists studying novel materials.

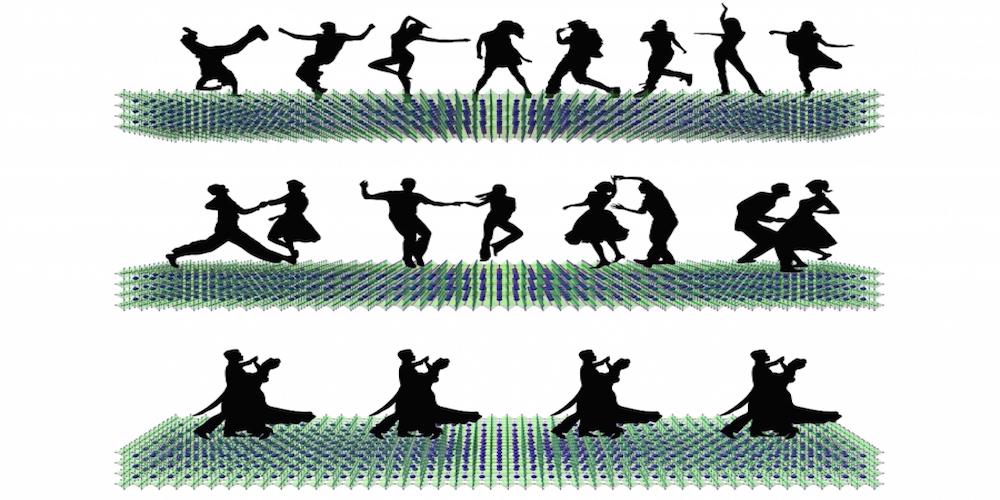

Swing-Dancing Electron Pairs

Superconductors are materials that permit electrical current to flow without energy loss. Their amazing properties form the basis for MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) devices and high-speed maglev trains, as well as emerging technologies such as quantum computers. At the heart of all superconductors is the bunching of electrons into pairs. Click the image to learn more about the "dancing" behavior of these electron pairs!

Froot Loops, Legos, and Self-Assembly

Self-assembly is the process by which individual building blocks—at the smallest level, atoms—spontaneously form larger structures. The structures they form depend on the size and shape of the building blocks, and on the conditions to which these building blocks are exposed. This can be demonstrated quite simply using breakfast cereal, or for more complex cases using specially prepared Legos.

Spin cant? Spin CAN!

In most magnetic materials, the magnetic moments of individual atoms are aligned parallel to one another and point in the same direction. In special structures called skyrmions and antiskyrmions, however, they are arranged in a spiraling pattern. Their stability and compact size makes skyrmions and antiskyrmions especially useful for encoding lots of data in a small space. But a few questions need to be answered before skyrmion-based technology can be used in your iPhone or other memory devices. First, why do these magnetic structures form in some materials and not others? How can we design a system where they will form? And how can we generate these structures on demand? Click to find out!