Related Posts

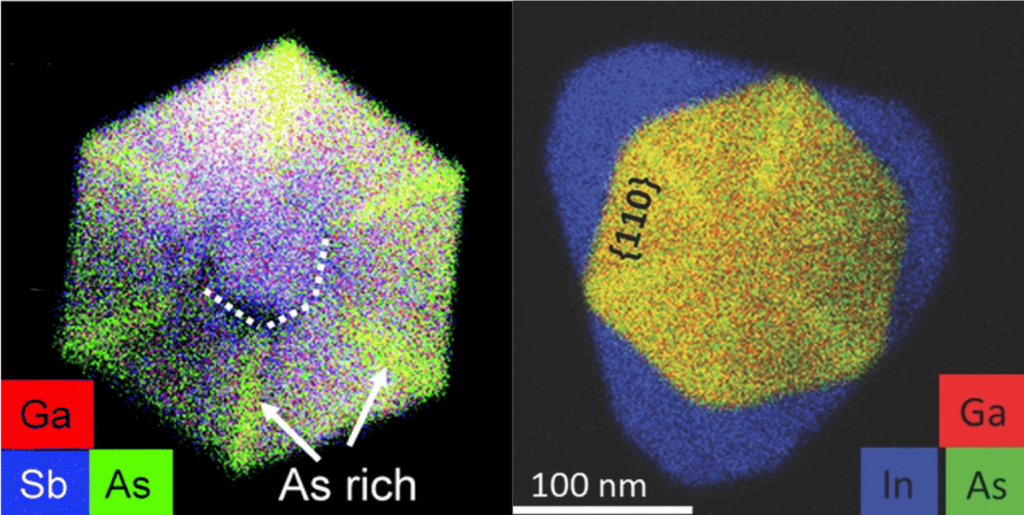

How can you fabricate a huge number of nanostructures in a split second? Self-assembly is a fast technique for the mass production of materials and complex structures. But before self-assembly is ready for prime time, scientists need to establish ways to control this process, so that desired nanostructures emerge from the unstructured soup of basic building blocks that are fast-moving atoms and molecules. Click here to find out how!

It’s a hot summer day. You desperately want something cold to drink, but unfortunately, your bottle of root beer has been sitting in a hot car all day. You put it into a bucket full of ice to cool it down. But it’s taking forever! How, you wonder, could you speed the process up? The same question is important for understanding how electronic devices work, and how we can make them work better by controlling the temperature of the electrons that power them. Read on to find out what a bottle of root beer in a cooler full of ice and a nanowire in a vat of liquid helium have in common!

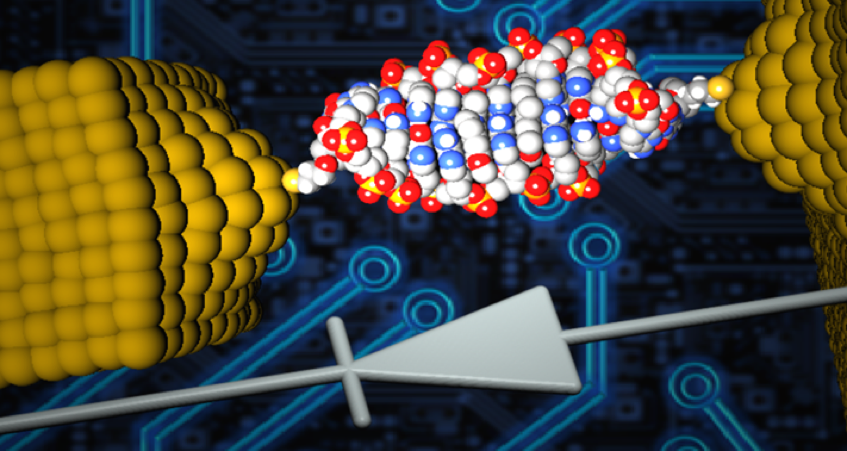

Diodes, also known as rectifiers, are a basic component of modern electronics. As we work to create smaller, more powerful and more energy-efficient electronic devices, reducing the size of diodes is a major objective. Recently, a research team from the University of Georgia developed the world's smallest diode using a single DNA molecule. This diode is so small that it cannot be seen by conventional microscopes.

More Funsize Fundamentals

Why do so many fluids behave counterintuitively? Many substances in our lives – like oobleck, slime, or Silly Putty – don’t quite behave the way we expect a fluid to, despite some fluid-like properties. These substances fall into a special category: non-Newtonian fluids. Scientifically, this term is a bit of a catch-all for any substances that have a complicated relationship between their apparent viscosity and the force applied to them.

The term may be unfamiliar, but we all have a sense for viscosity. We often think of it colloquially as the “thickness” of a fluid. It’s the property that makes honey pour so differently from water. Fluid dynamicists – scientists and engineers who study how liquids and gases move – tend to think of viscosity in terms of a fluid’s resistance to flowing or changing its shape.

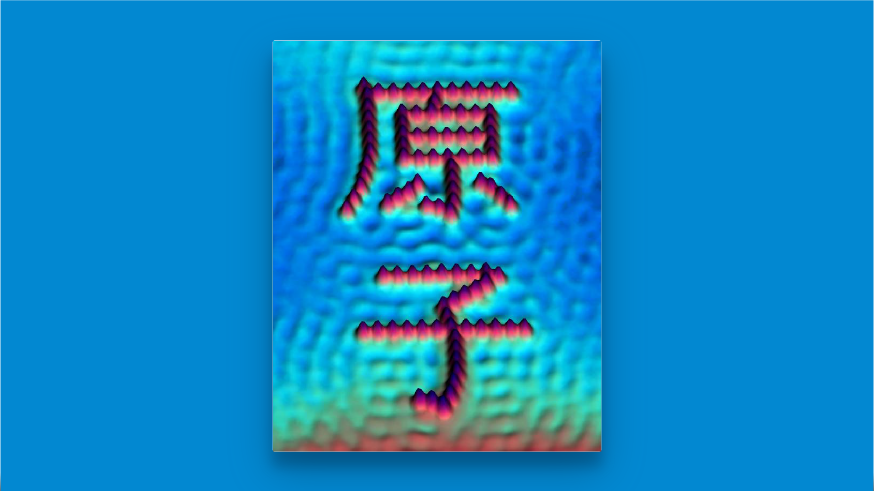

Have you ever wondered why some materials are hard and others soft, some conduct heat or electricity easily while others don't, some are transparent to light while others are opaque . . . and on and on and on? The material universe is vast and diverse, and while a material's properties depend in part on the elements it is made from, its structure—how it is built from its constituent atoms—can also have wide-ranging effects on how it looks, feels, and behaves. Diffraction is a method that allows us to "see" the atomic structure of materials. Read on to find out how it works!

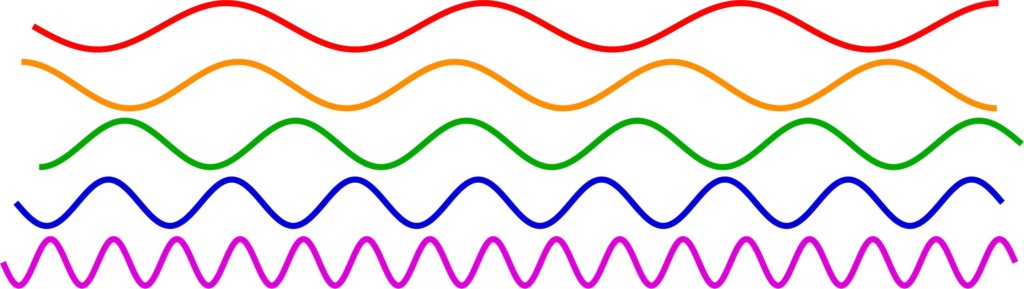

You’re lining up your phone to take a picture of your dog. Light comes down from the sun, bounces off the dog, and into your camera lens, allowing you to take the photo. Your eyes work similarly, taking in all the light particles, known as photons, that are scattering off of objects in the world. Most things “see” by detecting these bouncing photons, which is why both you and your phone have a hard time seeing anything at all when the lights are off.

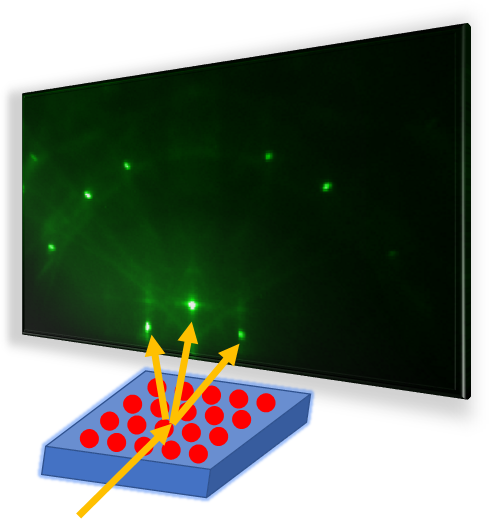

When light strikes a material, electrons may be ejected from the material. This is called the photoelectric effect, and it’s the basis for many different technologies that convert light energy into electrical energy to generate current. In addition, the photoelectric effect is useful to scientists studying novel materials.